Editorial notice:

This text was originally written for the Re-Public on-line journal, which focuses on innovative developments in contemporary political theory and practice, and is published from Greece. As the journal has ground to a (hopefully just temporary) halt under severe austerity pressures we decided to post the current first draft of the text on the Tactical Media Files blog. This posting is one of two, the second of which will follow shortly. Both texts build on my recent Network Notebook on the ‘Legacies of Tactical Media‘.

The second text is a collection of preliminary notes that expand on recent discussions following Marco Deseriis and Jodi Dean’s essay “A Movement Without Demands”. It is conceivable that both texts will merge into a more substantive essay in the future, but I haven’t made up my mind about that as yet.

Hope this will be of interest,

Eric

Charting Hybridised Realities

Tactical Cartographies for a densified present

In the midst of an enquiry into the legacies of Tactical Media – the fusion of art, politics, and media which had been recognised in the middle 1990s as a particularly productive mix for cultural, social and political activism [1], the year 2011 unfolded. The enquiry had started as an extension of the work on the Tactical Media Files, an on-line documentation resource for tactical media practices worldwide [2], which grew out of the physical archives of the infamous Next 5 Minutes festival series on tactical media (1993 – 2003) housed at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam. After making much of tactical media’s history accessible again on-line, our question, as editors of the resource, had been what the current significance of the term and the thinking and practices around it might be?

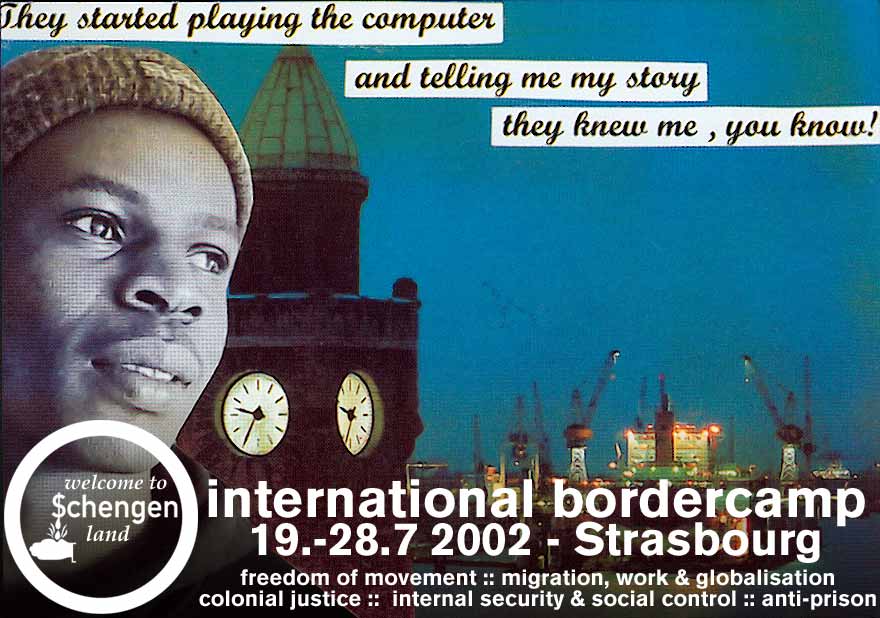

Prior to 2011 this was something emphatically under question. The Next 5 Minutes festival series had been ended with the 2003 edition, following a year that had started on September 11, 2002, convening local activists gatherings named as Tactical Media Labs across six continents. [3] Two questions were at the heart of the fourth and last edition of the Next 5 Minutes: How has the field of media activism diversified since it was first named ‘tactical media’ in the middle 1990s? And what could be significance and efficacy of tactical media’s symbolic interventions in the midst of the semiotic corruption of the media landscape after the 9/11 terrorist attacks?

This ‘crash of symbols’ for obvious reasons took centre stage during this fourth and last edition of the festival. Naomi Klein had famously claimed in her speedy response to the horrific events of 9/11 that the activist lever of symbolic intervention had been contaminated and rendered useless in the face of the overpowering symbolic power of the terrorist attacks and their real-time mediation on a global scale. [4] The attacks left behind an “utterly transformed semiotic landscape” (Klein) in which the accustomed tactics of culture jammers had been ‘blown away’ by the symbolic power of the terrorist atrocities. Instead ‘we’ (Klein appealing to an imaginary community of social activists) should move from symbols to substance. What Klein overlooked in this response in ‘shock and awe’, however, was that while the semiotic landscape had indeed been dramatically transformed (and corrupted) in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, it still remained a semiotic landscape – symbols were still the only lever and entry point into the wider real-time mediated public domain.

Therefore, as unlikely as it may have seemed at the time, the question about the diversification of the terrain and the practices of media activism(s) was ultimately of far greater importance. What the 9/11 crash of symbols and the semiotic corruption debate contributed here was ‘merely’ an added layer of complexity. In a society permeated by media flows, social activism necessarily had to become media activism, and thus had to operate in a significantly more complex and contested environment. The diversification of the media and information landscape, however, also implied that a radical diversification of activist strategies was needed to address these increasingly hybridised conditions.

To name but a few of the emerging concerns: Witnessing of human rights abuses around the world, and creating public visibility and debate around them remained a pivotal concern for many tactical media practitioners, as it had been right from the early days of camcorder activism. But now new concerns over privacy in networked media environments, coupled with security and secrecy regimes of information control entered the scene. Critical media arts spread in different directions, claiming new terrains as diverse as life sciences and bio-engineering, as well as ‘contestational robotics’, interventions into the space of computer games, and even on-line role playing environments. Meanwhile the free software movement made its strides into developing more autonomous toolsets and infrastructures for a variety of social and cultural needs – adding a more strategic dimension to what had hitherto been mostly an interventionist practice. In a parallel movement on-line discussion groups, mailing lists, and activity on various social media platforms started to coalesce slowly into what media theorist Geert Lovink has described as ‘organised networks’. [5] Or finally the rapid development of wireless transmission technologies, smart phones and other wireless network clients, which introduced a paradoxical superimposition of mediated and embodied spatial logics, best be captured in the multilayered concept of Hybrid Space. [6]

Our question was therefore entirely justified, to ask how the term ‘tactical media’ could possibly bring together such a diversified, heterogeneous, and hybridised set of practices in a meaningful way? It had become clear that more sophisticated cartographies would be necessary to begin charting this intensely hybridised landscape.

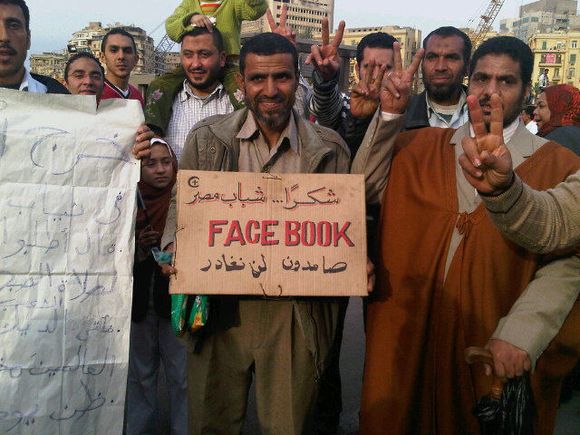

A digital conversion of public space

If the events in 2011 have made one thing clear it is that the ominous claim of Critical Art Ensemble that “the streets are dead capital” [7] has been declared null and void by an astounding resurgence of street protest, whatever their longer term political significance and fallout might be. These protests staged in the streets and squares, ranging from anti-austerity protests in Southern Europe to the various uprisings in Arab countries in North Africa and the Middle East, to the Occupy protests in the US and Northern Europe, have by no means been staged in physical spaces out of a rejection of the semiotic corruption of the media space. Much rather the streets and squares have acted as a platform for the digital and networked multiplication of protest across a plethora of distribution channels, cutting right across the spectrum of alternative and mainstream, broadcast and networked media outlets.

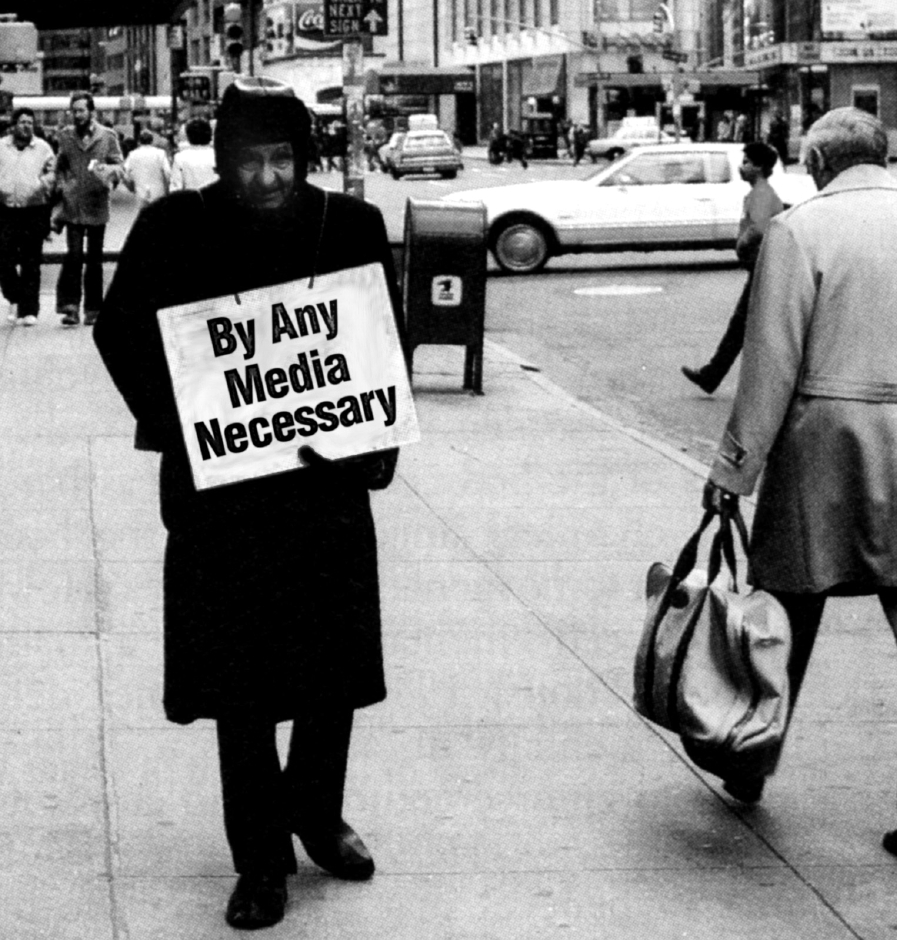

What remained true to the origin of the term ‘tactical media’ was to build on Michel de Certeau’s insight that the ‘tactics of the weak’ operate on the terrain of strategic power through highly agile displacements and temporary interventions [8], creating a continuous nomadic movement, giving voice to the voiceless by means of ‘any media necessary’ (Critical Art Ensemble). However, the radical dispersal of wireless and mobile media technologies meant that mediated and embodied public spaces increasingly started to coincide, creating a new hybridised logic for social contestation. As witnessed in the remarkable series of public square occupations in 2011, through the digital conversion of public space the streets have become networks and the squares the medium for collective expression in a transnationally interconnected but still highly discontinuous media network.

Horizontal networks / lateral connections

One of the remarkable characteristics of the various protests is not simply the adoption of similar tactics (most notably occupations of public city squares), but the conscious interlinking of events as they unfold. Italian activists of the Unicommons movement physically linked up with revolting students in Tunisia, Egyptian bloggers and occupiers of Tahrir Square linked up with the ‘take the square’ activists in Spain, who in turn expressed solidarity and even co-initiated transnational actions with #occupy activists in the United States and elsewhere. It is the first time that the new organisational logic of transnational horizontal networks that has been theorised for instance in the seminal work “Territory, Authority, Rights” by sociologist Saskia Sassen, has become so evidently visible in activists practices across a set of radically dispersed geographic assemblages.

Horizontal networks by-pass traditional vertically integrated hierarchies of the local / national / international to create specific spatio-temporal transnational linkages around common interests, but also around affective ties. By and large these ties and linkages are still extra-institutional, largely informal, and because of their radically dispersed make up and their ‘affective’ constitution highly unstable. Political institutions have not even begun assembling an adequate response to these new emergent political constellations (other than traditional repressive instruments of strategic power, i.e. evictions, arrests, prohibitions). Given the structural inequalities that fuel the different strands of protest the longer term effectiveness of these measures remains highly uncertain. The institutional linkages at the moment seem mostly limited to anti-institutional contestation on the part of protestors and repressive gestures of strategic authority. The truly challenging proposition these new transnational linkages suggest, however, is their movement to bypass the nested hierarchies of vertically integrated power structures in a horizontal configuration of social organisation. They link up a bewildering array of local groups, sites, networks, geographies, and cultural contexts and sensitivities, taking seriously for the first time the networked space as a new ‘frontier zone’ (Sassen) where the new constellations of lateral transnational politics are going to be constructed.

Charting the layered densities of hybrid space

Hybrid Space is discontinuous. It’s density is always variable, from place to place, from moment to moment. Presence of carrier signals can be interrupted or restored at any moment. Coverage is never guaranteed. The economics of the wireless network space is a matter of continuous contestation, and transmitters are always accompanied by their own forms of electromagnetic pollution (electrosmog). Charting and navigating this discontinuous and unstable space, certainly for social and political activists, is therefore always a challenge. Some prominent elements in this cartography are emerging more clearly, however:

– connectivity: presence or absence of the signal carrier wave is becoming an increasingly important factor in staging and mediating protest. Exclusive reliance on state and corporate controlled infrastructures thus becomes increasingly perilous.

– censorship: censorship these days comes in many guises. Besides the continued forms of overt repression (arrests, confiscations, closures) of media outlets, new forms are the excessive application of intellectual property rights regimes to weed out unwarranted voices from the media landscape, but also highly effective forms of dis-information and information overflow, something that has called the political efficacy of a project like WikiLeaks emphatically into question.

– circumvention: Great Information Fire Walls and information blockages are obvious forms of censorship, widely used during the Arab protests and common practice in China, now also spreading throughout the EU (under the guise of anti-piracy laws). These necessitate an ever more sophisticated understanding and deployment of internet censorship circumvention techniques, an understanding that should become common practice for contemporary activists. [9]

– attention economies: attention is a sought after commodity in the informational society. It is also fleeting. (Media-) Activists need to become masters at seizing and displacing public attention. Agility and mobility are indispensable here.

– public imagination management: Strategic operators try to manage public opinion. Activists cannot rely on this strategy. They do not have the means to keep and maintain public opinion in favour of their temporary goals. Instead activists should focus on ‘public imagination management’ – the continuous remembrance that another world is possible.

Beyond semiotic corruption: A perverse subjectivity

The immersion in extended networks of affect that now permeate both embodied and mediated spaces introduces a new and inescapable corruption of subjectivity. Critical theory already taught us that we cannot trust subjectivity. However, the excessive self-mediation of protestors on the public square has shown that a deep desire for subjective articulation drives the manifestation in public. The dynamic is underscored further by upload statistics of video platforms such as youtube that continue to outpace the possibility for the global population to actually see and witness these materials.

Rather than dismissing subjectivity it should be embraced. This requires a new attitude ‘beyond good and evil’, beyond critique and submission. A new perverse subjectivity is able to straddle the seemingly impossible divide between willing submission to various forms of corporate, state and social coercion, and vital social and political critique and contestation. It’s maxim here: Relish your own commodification, embrace your perverse subjectivity, in order to escape the perversion of subjectivity.

Eric Kluitenberg

Amsterdam, April 15, 2012.

References:

1 – See: David Garcia & Geert Lovink, The ABC of Tactical Media, May 1997, a.o.:

www.tacticalmediafiles.net/article.jsp?objectnumber=37996

2 – www.tacticalmediafiles.net

3 – Documentation of the Tactical Media Labs events can be found at:

www.n5m4.org

4 – Naomi Klein – Signs of the Times, in The Nation, October 5, 2001.

Archived at: www.tacticalmediafiles.net/article.jsp?objectnumber=46632

5 – Geert Lovink and Ned Rossiter, Dawn of the Organised Networks, in; Fibreculture Journal, Issue 5, 2005.

http://five.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-029-dawn-of-the-organised-networks/

6 – See my article The Network of Waves, and the theme issue Hybrid Space of Open – Journal for Art and the Public Domain, Amsterdam, 2006;

www.tacticalmediafiles.net/article.jsp?objectnumber=48405

(the complete issue is linked as pdf file to the article).

7 – Critical Art Ensemble, Digital Resistance, Autonomedia, New York, 2001.

www.critical-art.net/books/digital/

8 – Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, University of California Press, 1984.

9 – A useful manual can be found here: www.flossmanuals.net/bypassing-censorship/